Hey everyone, I’m excited to share a new motoko library:

ZenDB, an embedded document database that leverages stable memory to store and query large datasets efficiently. It provides a familiar document-oriented API, similar to MongoDB, allowing developers to store nested records, create collections, define indexes and perform complex queries on their data.

Links

- Mops: Mops • Motoko Package Manager

- Quick Start: GitHub - NatLabs/ZenDB: An embedded document database with native candid support for Motoko developers

- Documentation: ZenDB/zendb-doc.md at main · NatLabs/ZenDB · GitHub

- GitHub: GitHub - NatLabs/ZenDB: An embedded document database with native candid support for Motoko developers

The Problem

The Internet Computer’s heap is limited to 6GB, forcing data heavy applications toward multi-canister architectures which comes with their own set of complexities. Beyond capacity constraints, building data-heavy applications requires manually managing stable memory (layouts, allocations and serialization), choosing the right data structures for each of your query patterns, and implementing custom querying and indexing logic.

How ZenDB Solves This

ZenDB uses stable memory as its main data storage, providing up to 500GB capacity per canister. This unlocks the ability for data-heavy applications to use a simpler single-canister architecture. Instead of choosing between B-trees, hash maps, and creating custom indexes, you define your schema and let ZenDB handle the rest: efficient serialization, query planning, and index management behind a simple API.

Key Features

- Indexes: Support for multi-field indexes to speed up complex queries

- Full Candid Integration: Native support for Candid that allows you to insert and retrieve any motoko data type without creating custom serialization or type mappings

- Rich Query Language And Query Builder: Comprehensive set of operators including equality, range, and logical operations with an intuitive fluent API for building queries

- Query Execution Engine: Performance optimized query planner programmed to search for the best execution path that minimizes in-memory data processing.

- Pagination: Supports both offset and cursor pagination

- Partial Field Updates: Update any nested field without having to re-insert the entire document

- Schema Validation And Constraints: Add restrictions on what specific values can be stored in each collection

Real-World Test: ICP Txs Archive

To validate ZenDB works at production scale, I built a live dapp that indexes all 31M ICP transactions in a single canister. It fetches ICP transactions from the ledger canister periodically and indexes them using ZenDB.

Links:

- Frontend: https://24gro-qqaaa-aaaac-qcudq-cai.icp0.io

- Backend: https://dashboard.internetcomputer.org/canister/23hx2-5iaaa-aaaac-qcuda-cai

- Database: https://dashboard.internetcomputer.org/canister/2se4g-laaaa-aaaac-qcucq-cai

- Github Repo: txs-archive/backend/Backend.mo at main · NatLabs/txs-archive · GitHub

Setup: I created a Remote canister DB that exposes all the ZenDB methods. Then I set up a recurring timer function in the backend canister that calls the ledger canister every 5 minutes, and fetches the next batch of transactions since the last indexed one.

Performance: I spent about 3 weeks experimenting with this setup, trying to prevent as much downtime as possible. I hit the instruction limit a few times during indexing, causing the canister to stop. I also paused indexing a few more times to test different index configurations and benchmark them on various queries to find the ones that worked best. Eventually, I was able to get to a stable indexing rate of about 5000 txs / min. Without all the interruptions, it would have taken the dapp about 4 and a half days to index all 31 million transactions.

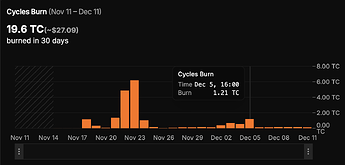

Cost: According to CycleOps, the total cost to index all transactions was 490 TC (~470 TC for the database canister, ~20 TC for the backend).

- Database

- Backend

Storage: The collection uses about 32 GB of stable memory to store all the transaction records and indexes. However, the canister is currently 44 GB because it retains the allocated pages of some deleted indexes. The library also uses some heap memory (about 1.7 GB here) for document caching, in memory data processing, document validation, serialization and index key computation.

Queries: The backend exposes a function called v1_search_transactions() that handles queries from the frontend to the DB canister which uses these 8 compound indexes to speed up the execution of those queries.

What’s Next?

![]() Feel free to stop here if you’re not interested in the technical details!

Feel free to stop here if you’re not interested in the technical details! ![]()

The rest of the post dives into the technical architecture, design decisions and performance of ZenDB. If you’d rather:

- Get Started: Check out the readme

- See The Full Documentation: ZenDB/zendb-doc.md at main · NatLabs/ZenDB · GitHub

- Keep Reading: Continue below for the technical deep-dive

Architecture Design

ZenDB is a stable instance that consists of multiple databases, which in turn contain multiple collections. The actual data and indexes are stored in collections, and databases act as namespaces for grouping related collections.

Each collection uses a MemoryB+Tree for the document storage and each document is assigned a unique ID. To speed up queries, you can create secondary indexes (also MemoryB+Trees) that store concatenated field values as keys and document IDs as values, for quick range scans and lookups that point back to the original document.

There’s no hard limit to the number of databases, collections, or indexes that can be created. However, each index increases the instruction cost of insertions.

Internal Query Workflow

When executing a query, ZenDB follows this optimized workflow:

- The query is parsed and validated against the collection schema

- The query plan generator analyzes available indexes and query patterns, picking the best one for each group of filter and sort conditions.

- For indexed queries, the system chooses between:

- Index Scan: Direct B-tree traversal for equality or simple range queries

- Hybrid Approach: Combining index scans with in-memory filtering for complex queries

- Union or Intersection: Merging results from multiple index scans (usually required for nested

#Andand#Oroperations)- Bitmap: Loads IDs from each index scan into independent bitmaps and finds the intersection between them

- K-merge: Loads IDs from each index scan into iterators, compares values at the top of all iterators, and returns values in sorted order

- Results are processed, sorted if needed, and paginated according to query parameters

Finding the union or intersection of multiple index scans allows ZenDB to handle complex queries efficiently, even with large datasets, by minimizing the amount of documents that need to be deserialized for internal filtering and sorting.

Important Note: Currently, no automatic indexes are created for your data. You’ll need to create your own indexes when defining your collection and schema. If no indexes exist that can satisfy a query, ZenDB will run a full collection scan, which is likely to hit the instruction limit for a dataset with as little as ten thousand records.

Orchid - Order-Preserving Encoding

ZenDB uses a custom order-preserving encoding format called Orchid to serialize index keys. This allows us to create composite index keys that maintain the sort order of multiple fields for efficient range scans and lookups in the B-tree indexes.

Orchid supports all Motoko primitive types in addition to Option, Text, and Blob types. Complex types like Record and Array are not supported as index fields, and Variant types are only partially supported (only the tag is indexed, not the inner value).

Unbounded types like Text and Blob are prefixed with their length to ensure correct ordering. The length prefix takes up two bytes, which means the maximum size for indexed Text and Blob fields is 65,535 bytes. The Principal type uses a one-byte length prefix, limiting indexed Principal fields to 255 bytes.

Unbounded Nat and Int types are converted to Nat64 and Int64 respectively before being encoded. While this is simpler to implement than a fully unbounded encoding, it does limit the maximum storable value. This implementation is sufficient for most cases, but we can extend the encoding format to support unbounded number types if there’s enough demand, as it’s designed to be extensible.

Here’s a link to the Orchid source code. I’ll also make this module its own Mops library if there’s interest.

Pagination: Cursor vs Offset

ZenDB supports both offset and cursor pagination, but they have different performance characteristics.

Offset pagination lets you define skip and limit parameters:

ZenDB.QueryBuilder()

.Where("age", #lt(#Nat(18)))

.Skip((page - 1) * page_size)

.Limit(page_size)

However, offset pagination becomes problematic at scale because although you receive the results after the offset, the database must still process all documents prior to your offset position before returning the requested results. Given enough entries in your database, your pagination results will eventually hit the instruction limit as all the preceding documents are still processed. And as a result, you would not be able to retrieve all the pages for your query.

Here’s an example of two queries using offset pagination:

-

A filter query on page 300 (txs 2990 - 3000) - ZenDB Indexing Test

-

The same query hitting the instruction limit on page 400 (txs 3990 - 4000)- ZenDB Indexing Test

Cursor pagination solves this by returning a pagination token in the search response:

// First request

let #ok(res) = collection.search(

ZenDB.QueryBuilder()

.Where("age", #lt(#Nat(18)))

.Limit(10)

);

Debug.print(res.documents); // first page

// Next request

let #ok(res) = collection.search(

ZenDB.QueryBuilder()

.Where("age", #lt(#Nat(18)))

.Limit(10)

.PaginationToken(res.pagination_token)

);

Debug.print(res.documents); // next page

The token encodes the query state, eliminating the need to reprocess earlier documents. You can traverse the entire result set by making consecutive calls for the next page without ever hitting the instruction limit. This eliminates the ability to randomly access pages while providing reliable pagination that scales with large datasets.

We can retrieve the documents in the previous offset query that failed using cursor pagination. To do this we just set the limit to a number that can be executed within the instruction limit. I’m gonna do 3000 because we know that those transactions can be retrieved by the offset pagination.

- ZenDB Indexing Test

After the first result, retrieve the next set of results by clicking next or page 2 and the txs between 3990 and 4000 that we couldn’t retrieve before will be included in the results.

Current Scope & Limitations

- Single Sort Field: You can only sort by one field; multi-field sorting is planned

- No Aggregations: Sum, count, and other aggregation functions are not yet supported

- Limited Array Support: Arrays can be stored but cannot be indexed or have operations performed on nested elements

- No Full-Text Search: Text-based full-text search and pattern matching within indexes is not supported

- Complex OR Queries: Queries with many OR conditions may have suboptimal performance due to the internal merge required between independent index scans on different indexes

- Query Planner: May not always select the optimal index for very complex queries (recommend benchmarking and adjusting indexes accordingly)

- Schema Updates: Schema migrations are not yet supported; changing an existing collection’s schema requires creating a new collection and migrating data manually

- No Built-In Backups: Internal and external canister backups are not currently supported

- Supports Ascending Index Fields Only: Queries in descending order are supported, but indexes can only be created in ascending order at this time. We use reversible iterators internally, so there is no performance difference when querying in descending order.

Challenges & Design Decisions

Serialization Overhead

Storing data in ZenDB involves Candid encoding and schema validation. Compared to a simple B-tree without these internal data mutations and safeguards, ZenDB uses approximately 10x more instructions per insertion.

This overhead is inherent to any database system. While serialization is known to be expensive and has traditionally only been applied to JSON and Candid decoding of select entries, ZenDB requires it for all entries in order to access nested record fields during query execution and indexing. The serialization library has been optimized as much as possible, though native Blob.concat() and Blob.slice() operations in Motoko could significantly improve performance. Many serialization operations add bytes to a buffer and convert them to blobs, which these functions could replace directly.

The 10x overhead is acceptable given the benefits: complex queries, stable memory scaling, and index-driven performance gains. Whether this trade-off is worthwhile depends on your use case and access patterns.

Choose ZenDB if:

- You need stable memory capacity

- You need to create complex queries on your data

- Your workload is read-heavy: historical data, logs, analytics dashboards, and time-series data that rarely change but require frequent querying benefit significantly from ZenDB’s indexing

- You want the simplicity of a single canister architecture

Consider a heap B-tree if:

- Instruction cost is critical and your data fits in 6GB

- Your access patterns are simple key-value lookups with no need for complex queries

Memory Page Deallocation

When testing different index configurations for the txs_archive, I experimented to find the optimal set. Some indexes proved less useful and were deleted. Currently, Motoko doesn’t support deallocating pages within stable memory regions. As a result, the canister continues to pay for the memory of those deleted indexes.

To mitigate this, deallocated regions are tracked in a list to be reused by future indexes and collections. However, this only prevents future waste; existing unused pages remain allocated.

The txs collection stores 32 GB of actual data, but the total allocation is 45 GB, leaving 13 GB unused from deleted indexes. To avoid this, benchmark your index strategy on a small subset of your data before committing to indexing millions of documents.

Memory Collection & Supporting Libraries

ZenDB uses the memory-collection library, which provides three stable memory data structures: MemoryBuffer, MemoryBTree, and MemoryQueue.

Building on the original MemoryBuffer post, I’ve moved it into the memory-collection lib and improved the performance of the MemoryRegion allocator used for managing freed memory blocks. It now uses a single MaxValue B+Tree instead of two separate B-Trees, and switched from best-fit to worst-fit allocation. This change reduces the number of tree traversals required per allocation and retrieves the largest free block at constant time, making reallocation faster than best-fit. Additionally, I added support for merging adjacent free blocks to reduce fragmentation over time.

Several supporting libraries were also improved or created during development:

- Serde: Added a

TypedSerializermodule that uses 50 and 80% fewer instructions for repeated serialization/deserialization on the same data type - BitMap: Faster set operations for index intersection and union

- ByteUtils: Fast number to byte conversions and vice versa. Including order-preserving byte serialization for maintaining sorted order in blob form.

- LruCache: Added support for custom eviction handlers

These are published on Mops and available for use in other projects.

What Helped During Development

Mops: Made benchmarking and local testing between libraries trivial.

VSCode Motoko Extension: All the features from this extension makes Motoko feel like any of the more mature languages and it’s a bliss to code in.

CycleOps: Handled automatic top-ups across multiple canisters, which was essential for backfilling txs_archives.

Motoko Language: Massive improvements from the motoko team. Some I would like to highlight:

- Accessing the canister ID in the top-level of the actor class is a lot cleaner than exposing a public function that’s called during initialization.

- The new migration syntax explicitly handles schema upgrades for non-mutable stable variables, allowing you to retain the same variable name across versions

- Recent additions of

explodeNatXand nativeBlob.get()primitives significantly reduced the performance overhead of blob operations

Next Steps

I plan to continue testing ZenDB, improving its performance and adding new features. If ZenDB sounds like it’s right for your use case, give it a try and let me know if you encounter any bugs or have any feature requests. Feel free to open an issue on GitHub or add them in this forum post. Any suggestions, feedback, or contributions are welcome as well.

- Report Issues: GitHub · Where software is built